The founding of University College (UC) is closely tied to the colonial project of Canada, and not every student has felt welcome, or at home, within the whimsical “medieval” architecture of the building. For instance, Indigenous students have reported that they were reminded of residential school when they encountered the architecture for the first time. Canada and its institutions have a complex history, but the UC community has attempted to create a counterbalance to some inequities of the past with investments in sexual diversity studies, queer and transgender research, and financial support for Black and Indigenous students. To continue to redress colonial legacies, the Art Museum has been working with University College to install newly acquired artworks by artists Dana Claxton and Syrus Marcus Ware. The two artworks mark a newly energized chapter in the presentation of art at University College, which aims to welcome diverse people from all walks of life.

Members of the UC community, including the Art Museum and Principal Markus Stock, are devoted to continuing to interrogate the legacy of the university and to taking steps to create a more egalitarian and accessible environment for students and faculty. In the pursuit of this endeavour, UC not only directs funding and scholarships to Indigenous and Black students but is also attentive to the symbolic side of welcoming students to build their own communities and a sense of belonging. It is hoped that the installation of the new artworks in the hallways and gathering spaces of UC will encourage students to discuss the art and the ideas each piece introduces to the space.

“If we’re aiming at interrogating the university as a space, and whether that space is really inclusive and open to modification, then it’s important that people notice [the artworks] and create community around noticing,” said Principal Stock.

“It is a bit of a provocation—it’s hard for people not to take a stance. Responses might be varied, but provocation is exactly what art should do,” he explained. “If people want to and are willing to explore it, there’s a lot to unpack there.”

RED ON RED: ODE TO GRAMSCI

Red on Red: Ode to Gramsci, 2017

ink on polyester

Gift of the artist, 2022

(2017) BY DANA CLAXTON

Dana Claxton is a Hunkpapa Lakota artist who is known for her work with film, photography, installation, and performance. Her piece, Red on Red: Ode to Gramsci (2017) will be installed by the Art Museum at University College, where students and faculty will encounter it daily. Red on Red is a collection of eight banners of red fabric printed with dark, sans-serif text. The flags will hang in a corridor where students will pass by them on their way to classes, meals, and social gatherings. The Art Museum’s acquisition of this piece adds Indigenous art to the collection, and complements critical discussions about decolonization of university spaces.

Claxton defies the expectations non-Indigenous viewers often have of Indigenous art—that is, to be recognizable cultural artifacts. Instead, she uses poetry and text to activate a visual discourse. While not easily legible to viewers, the banners have hues of cultural coding in Indigenous and Gramscian thought, the latter a theory of cultural hegemony. The text on each flag represents foundational Gramscian ideas, but the structure and form of the words have been given a creative twist by the visual and poetic nature of the series. Each flag features a phrase, such as Let the Poem Limp; Luxury mammal seeks trained guerilla; or Party Your Slogan. These are as mysterious as they are compelling and cannot be easily interpreted. Other phrases are more straightforward but no less thought provoking, such as Raise Your Political Level, and Understand Your Historical Value. These provocations demand engagement rather than offer passive legibility.

As an unlimited edition, variations of the work have been previously exhibited elsewhere in Canada in different forms—on walls, suspended in halls, in publications, and even in performance. This multimedia way of exhibiting an edition suits the concepts addressed by the work especially well. The same red thread (or as Claxton says, “both the red thread and the red sinew”) runs through each iteration of Red on Red and unifies a range of media and ideas, which will soon include UC spaces. Claxton has stated that her identity as a Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux woman informs the work, suggesting that Indigenous knowledges shaped by the collective and commons run parallel to Gramscian ideas.

As noted earlier, Gramsci is well known for his theory of cultural hegemony, which describes how cultural institutions such as universities use and maintain dominant forms of power in societies structured by capitalist economies. Claxton’s poetical flags, in the context in which they will be installed at UC, can suggest a critique of the kind of institutional power held by the university—if not also by Gramsci’s work—especially when considered from an Indigenous perspective that has been historically and theoretically excluded. This critique does not address a specific point of view, but instead, points out the way institutions such as universities yield and wield dominance and power in society, allowing them to legitimize and transmit ideas (or delegitimize and halt ideas). Ideas are the vehicle that institutions such as universities use to shape the values and norms that maintain dominant forms of power through generations.

The presence of Claxton’s artwork in the UC building will call attention to the processes of university education itself. It de-automatizes the way art and poetry interact with the university space and poses a historical question about the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives. Displaying the artwork is important to do, because as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has reported, a lack of historical knowledge by Canadians has had serious consequences for Indigenous people in Canada. Sherene Razack has written, in her analysis of how settler-colonial institutions have subjugated Indigenous people, that to historicize is to engage with “a process that begins by asking about the relationship between identity and space.” Razack terms this process “to unmap.”

Haudenosaunee scholar Mishuana Goeman uses a similar term, “remap.” It describes the creative acts Indigenous women do that expose the ways Euro-Canadian culture conceptualizes itself and “others,” while also redefining colonized subjects. The process of remapping Indigenous art within the university does not require the viewer to have complete knowledge of Claxton’s intended meaning. After all, whoever can or should possess and control Indigenous knowledges is a pertinent question in reconciliatory and decolonial processes, especially in universities. Claxton’s piece implores the viewer to think deeply, not necessarily to obtain a predetermined answer.

“There is something inscrutable about them, and something that cannot be deciphered,” said Principal Stock. “It’s not that you, the beholder, don’t understand this art if you don’t know what the sentence means.”

SELF PORTRAIT WITH COTTON BALLS

(2006) BY SYRUS MARCUS WARE

Syrus Marcus Ware is a Black, transgender artist and a Vanier scholar who works with painting, installation, and performance. His activism explores social justice frameworks and Black activist culture, and he is a founding member of Black Lives Matter Canada. The Art Museum’s acquisition of his work Self Portrait with Cotton Balls (2006) enables a transformation of space on campus, providing the opportunity for engagement by faculty and students in multiple academic units, especially in Sexual Diversity, Women and Gender, Transnational and Diaspora studies, as well as contemporary Canadian art and international art. The addition of this painting to the collection adds to the representation of art and artists who work in Toronto and complements critical reflections on BIPOC, disabled, and LGBTQ perspectives and counter-narratives.

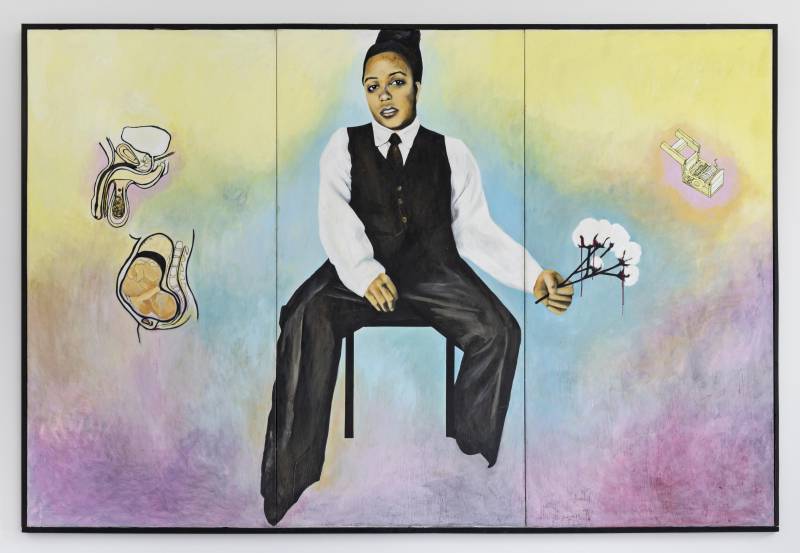

The painting is a triptych, painted across three panels. Ware is depicted sitting in a chair, wearing an old-fashioned men’s suit, and looking boldly out at the viewer. His hand holds a branch of cotton balls out into the right panel of the triptych. The sharp edges of the mature cotton burrs drip with blood, which represents his father’s lived experience labouring in cotton fields, as well as deeper histories of the transatlantic slave trade. A small cotton gin floats above the cotton branch, isolated on the picture plane against a background of pastel colour.

Syrus Marcus Ware (b. 1977)

Self Portrait with Cotton Balls, 2006

acrylic and marker on canvas

Purchased by the University of Toronto Art Committee, 2022

The cotton gin is popularly thought of as a device that historically eased the labour associated with cotton crops. In fact, the opposite is true — the engine made cotton more profitable, which increased the demand for production and for greater numbers of enslaved labourers. The increased pressures of cotton production imposed more cruelty on enslaved Black workers in cotton-growing regions of America. The histories that accompany this deeply symbolic iconography may not be decipherable to every viewer. Nonetheless, for every viewer who recognizes the cotton gin, their own position affects their interpretation of the image and the histories that the image recalls. On the opposite side of the picture, Ware’s toe steps over the line between canvases to point to the left panel of the triptych. On this panel, two drawings of human reproductive organs, recognizable as male and female, float in a colour field of pastel hues. The female uterus contains a late-term fetus turned headdown, a position implying impending labour and birth. The viewer is compelled to interpret some symbolic or codified meaning from these images, but many narratives are possible to imagine. Do these images symbolically refer to the artist himself, a transgender man in a process of emergence? Is the idea of labour a double entendre, to connect with the images of cotton and further discuss personal, generational, and cultural histories of Black people’s labour? Is it significant that the cotton blossoms—the reproductive organs of the plant—drip blood on one side of the picture, while the child on the other side is almost ready to be born?

The boundaries between panels are significant because they divide the painting topically as well as spatially, into Black history, human sexuality, and the individual who lives in and between both histories. Often, viewed through the lens of the dominant Euro-Canadian culture, differences such as race, gender, and sexuality seem to be clearly defined categories that divide people into separate groups. Ware sits between conspicuous, categorical understandings of being human, but his portrait also crosses the defined boundaries to unify his three canvases into one picture.

Ware’s self-portrait is displayed in the Senior Common Room at UC, a semi-secluded location where, at different times, members of the UC community can either relax in a quiet space or gather for social events. This places the portrait in a dual context, as a piece that motivates conversation and questions in a crowd, but also encourages quieter contemplation by individuals at rest.

Whatever each viewer’s response may be, Principal Stock says, “I think [the university] being too comfortable in a certain identity construction that has been around for decades, or even longer, doesn’t serve those who have not seen themselves in these spaces. Talking about this painting—what I don’t like about it, what I like about it, what I think it might mean—potentially is in the vicinity of those questions that we need people to ask about university in general, and in the space of this university.”

The next time you walk through the halls of the University College or visit the lounge where these works are installed, look up and notice the art. Whoever you are, wherever you come from— allow yourself to be unsure and ponder for a while.

Rowan Red Sky (member of Oneida Nation of the Thames) is a PhD student in the Art History program and the collaborative Book History and Print Culture specialization at the University of Toronto. Her research investigates the way Indigenous multimedia and performance artists have responded to stereotypical images, while also maintaining their own cultural continuity and connections to land. Environmental history and Indigenous perspectives guide her work, which includes creating visual and performance art and archival and curatorial projects.